When Femi Claudius Cole decided to form a political party, to address what she saw as Sierra Leone’s slow economic development and poor governance, she knew it would be tough. A former nurse, she had no experience in politics and people told her no one would vote for an unknown. But she could not have predicted quite how gruelling it would be: leaving her spending time in jail and fighting for her reputation.

The Unity party, registered by Cole in 2017, failed to win any seats in the 2018 general election. But she persevered, travelling around the country offering medical treatment with a surgeon, giving interviews and building up a social media following. In 2021 she co-founded the Consortium of Progressive Political Parties, an opposition alliance. “People thought that once I lost, I would disappear into thin air – they didn’t know me,” she says.

In July 2022, when women organising a rally to protest at the soaring cost of living asked for her backing, she agreed, allowing them to make placards in her office. They planned to dress in black and hold a prayer service. But the day before the rally, armed police surrounded Cole’s house.

“There were so many of them they blocked the whole street,” she says. The police told her she was being “invited” to answer questions at the Criminal Investigations Department.

Cole went to the police with her lawyer, was accused of inciting the protests and detained for four nights. They confiscated her passport, which has yet to be returned.

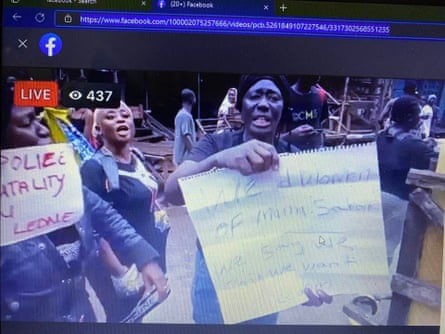

When the nationwide “Black Monday” protests, which also involved a strike by businesses, street traders and public transport, went ahead the following day, 54 women were arrested in Sierra Leone’s capital, Freetown, for participating in an illegal gathering (although Cole says they had sought permission to march). Other women were beaten and taken to hospital.

The experience shook Cole but strengthened her resolve. “I was thinking ‘should I have discouraged the women from protesting, helped them to silence themselves?’ But I knew the women had a point and the constitution supports protest,” she says.

“So I came out way bolder, [thinking] I know the worst you can do to me. I realised I have a responsibility. I cannot now go into self-protection mode – I belong to these people.”

The following month, protests against economic hardship erupted in Freetown, and this time they turned violent. Hundreds of people took to the streets and at least 27 died in clashes, including six police officers. Once again, armed police surrounded Cole’s house.

That same day, across the city, another female politician was being intimidated by the police presence outside her home. Yvonne Aki-Sawyerr was Freetown’s mayor and had won accolades for positioning the city at the forefront of the battle against the climate crisis in Africa. But Aki-Sawyerr’s popularity has also earned her enemies. No charge was brought after she was blamed for the August protests, but in September she was charged with disorderly behaviour and obstructing the police after going to support one of her councillors who had been arrested at Lungi airport. Her case is ongoing.

Cole and Aki-Sawyerr point out the irony of finding themselves targeted with false allegations while MPs debated the gender equality and women’s empowerment bill. “They do a lot of whitewashing. This gender bill is totally at odds with the way women are treated. We can’t be seen, we can’t be heard. The intimidation is suffocating,” says Aki-Sawyerr.

In January 2023, the landmark bill became law, stipulating that 30% of candidates for elected positions and 30% of presidential appointees must be women. Currently only 13% of MPs, and 17% of ministers are women.

Signing the bill into law, President Julius Maada Bio said: “Women’s economic empowerment and protection are not political rhetoric. Empowering women is essential to the health and social development of families, communities and countries.

“Women can reach their full potential when they live safe, fulfilled, productive lives. The future of Sierra Leone is female.”

Campaigners hailed the law as a watershed moment. As well as increasing political representation, the law extended maternity leave, improved women’s access to finance, introduced equal pay and stipulated a 30% female quota of staff in private companies with more than 25 employees.

“This is the first time Sierra Leone has had such an act and that is why we are happy,” says Sahr Kendema, of the Campaign for Good Governance, which had introduced the yellow-ribbon campaign in support of the gender equality bill.

But Kendema says the law’s wording gives the president a get-out cause when it comes to appointing ministers and other key roles such as ambassadors. It says the president “may” appoint women to 30% of positions. “We see this as a start … a working document. Our next advocacy is to change the wording of ‘may’ to ‘shall’,” he says.

There are also concerns that nominees will not necessarily be elected, especially since the election on 24 June will be based on proportional representation for the first time. The bill only makes it mandatory for political parties to nominate a female candidate, not to choose one, says Sudie Sellu, women’s empowerment lead for the Irish aid agency Trócaire. “We need nominations that will end up winning.”

Money is another barrier for women, says Cole. Candidates have to pay more than 3,600 new leones (£128) to get on the ballot sheet (annual GDP in 2021 was £380 a head). “How do we, as a relatively small young party, present a list of people prepared to pay [that much]?”

after newsletter promotion

Even if the minimum 30% target is achieved in both elected and appointed positions, women say the country has a long way to go in addressing sexist attitudes, especially towards women in power.

Cole and Aki-Sawyerr have paid a high price for speaking out. The Unity party has been barred from the elections for not following protocol in polls – an allegation that Cole disputes. “I’ve been blacklisted,” she says. “The last time I was at a meeting, the deputy minister of justice looked at me and asked ‘why is she still here?’ They thought they had got rid of me.”

In February the government gave all mayors until 1 March to vacate their offices ahead of June’s elections, two months earlier than usual, a move that Aki-Sawyerr, a member of the main opposition party, the All People’s Congress (APC), believes was designed to oust her. “Twenty-one other councils [affected], just to get me,” she says. “They are obsessed with removing us from the political space.”

Catherine Zainab Tarawally, an opposition MP from the north, says she is often told to “get back in the kitchen”. “Sierra Leone is a patriarchal and chauvinistic society. Women make up 52% of the country but we are still fighting to grasp what is ours.”

Tarawally, advisor to the female caucus and chair of the gender affairs committee, says she survived her first term in parliament by giving as good as she gets.

“They call me the iron lady – if I want something, I fight for it,” says the MP, one of only seven women among 59 APC parliamentarians. Successfully lobbying for tougher sentencing for serious sexual offenders in the 2019 Sexual Offences Act and the 2020 Cyber Security and Cyber Crimes Act are among her proudest achievements.

Another MP, Emilia Lolloh Tongi, became the first woman to stand as an independent in the 2018 election. After working in France, she decided to return home to eastern Sierra Leone, an area lacking basic infrastructure, including health and education facilities.

The story of a woman who died walking to a clinic while in labour, was a terrible illustration of Sierra Leone’s woeful record on maternal deaths – and the moment Tongi knew she wanted to serve her community. “It was so upsetting,” she says. “She was found lying on the road holding her baby’s feet.”

Tongi was warned that politics was “bloody and violent” and during her campaign her house was attacked and she was threatened daily by supporters of rival candidates. But when she beat the two main parties to win her seat the abuse turned to admiration – especially after her rousing maiden speech.

“They portray politics as something bloody because they don’t want us to be there. I thought politics was extraordinarily difficult, but it has been a great discovery.”

This year she is standing for the ruling Sierra Leone People’s party, and hoping that the improvements she has helped bring about in her constituency – including building a health centre and a school, bringing solar lights to villages, introducing a microcredit scheme for women, and launching a radio station – will help her win enough votes on 24 June.

“For the past 60 years, nothing happened [in this area]; I have modernised it. Parliament should have 90% women – we are not there to get fancy cars,” says Tongi. “Women have been criticised as weak, but now look at us. I have proved anything men can do, women can do it better.”

1 year ago

101

1 year ago

101

English (US)

English (US)