Angels from the spirit realm told Hilma af Klint that becoming a vegetarian would fuel her creativity. This great Swedish artist, whose pioneering works predate the first purely abstract compositions by the likes of Kandinsky and Mondrian, was used to taking advice from higher forces. She was a member of the marvellously named De Fem (the Five), a group of female artists who organised seances and made art under the guidance of spirits called Ananada, Amaliel, Clemens, Esther, Georg and Gregor. “There are foods that cause lethargy in the body,” Af Klint once wrote. “There are foods that sustain the body, and finally there are foods that come from the opposite direction, that sustain the body in a non-material way.”

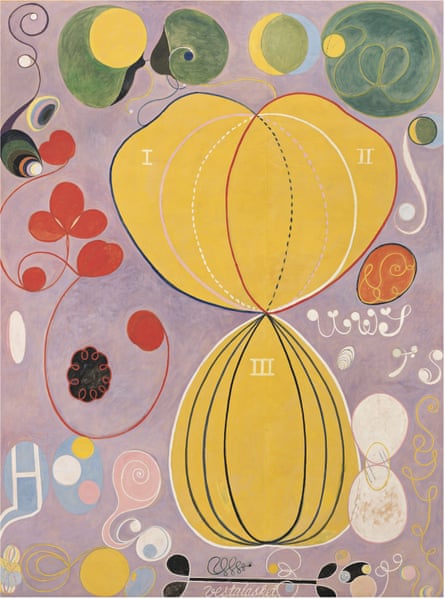

I think about those words as I stroll with Briony Fer through one of the most beautiful rooms in Europe, a gallery at Stockholm’s Moderna Museet containing a series of paintings called The Ten Largest. Perhaps without a vegetarian diet, these grand grids and intersecting circles – suggesting shells, wings, swans, flowers and sunbursts – might never have existed. Nor, perhaps, would her proto-pop art palette of sunny oranges, feminine blues and masculine yellows (expressing physical and spiritual love) have been so thrilling.

Af Klint made these in the course of 40 days from 1906 to 1907, while Picasso was painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, considered to be the first cubist painting, and while Mondrian and Kandinsky were still mired in representational art. They have now been shipped to Tate Modern for an exhibition that Fer, art professor at the University of London, is co-curating. It’s called Hilma af Klint and Piet Mondrian: Forms of Life – and from now until September, quite possibly, Europe’s most beautiful room will be in London.

The Ten Largest were part of a series of 193 works called Paintings for the Temple that were to be displayed in a custom-built spiral-shaped building and would be instrumental, spirits told Af Klint, in “communicating images to humanity of the life that exists beyond everything”. It was perhaps the strangest commission in art history.

Af Klint, like her mentor Rudolf Steiner, the charismatic Austrian founder of the Anthroposophical Society, took inspiration from scientific advances such as the discovery of X-rays, radiation, electrons and Darwin’s evolutionary theory. They believed such breakthroughs confirmed their occult view that all forms of life are one and the world is ruled by forces hidden to the naked eye. Af Klint wanted to make them visible.

Fer adores these paintings, but not the occultism that underpins them. “Even if she thought she was told what to do by angels,” she says, “that doesn’t explain why they are so fabulous.” To appreciate the work properly, believes Fer, you need to have some critical distance from her mysticism.

Her mysticism certainly hasn’t helped Af Klint’s posthumous reception. When her grand-nephew Johan offered her paintings to the Moderna Museet in the early 1970s, the director turned them down as soon as he heard she was a medium. Other cultural gatekeepers erased her from art history. In 2012, when New York’s Museum of Modern Art staged Inventing Abstraction 1910-1925, Af Klint was not even included as a footnote.

The situation was not helped by the artist’s own stipulation that none of her works – which number 1,300 – could be publicly displayed until 20 years after her death. The angels advised her the world was not ready. So she was deleted from the grand narrative of modern art, until the Moderna Museet staged a retrospective in 2013. But the real breakthrough came in 2019 when New York’s Guggenheim staged a blockbuster show, with her paintings fittingly displayed in Frank Lloyd Wright’s spiral building, for all the world like the temple for which she had made her paintings a century earlier.

Tate Modern’s Af Klint-Mondrian show may seem an unlikely pairing. After all, though the two died in the same year, they never met. Yet they were unwitting soulmates: both dined at the same vegetarian restaurant in The Hague, a female-run establishment called Pomona where feminists, theosophists (believers in a spiritual reality that could be accessed via intuition and revelation), anti-carnivores and modernist artists congregated. Mondrian became a vegetarian on the advice of Man Ray, in order to stem atherosclerosis and arthritis. Later he switched to a diet, devised by US doctor William Howard Hay, that counselled against certain combinations of foods. “What [Mondrian] had previously encountered in jazz he now encountered in the Hay diet,” wrote the artist’s biographer Hans Janssen. “Eating was like composing, based on the combination of mutually exclusive, negating and complementary elements.”

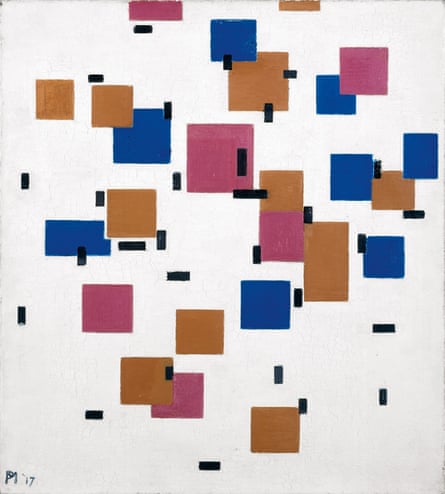

In the 1920s, Mondrian painted in his studio to the sound of boogie-woogie from his record-player and it fed into his work. Today, there’s even a Mondrian playlist on Spotify. In this, Mondrian was rebelling against his Calvinist father Pieter, headteacher of the primary school that Piet attended. Calvinism frowned on the use of musical instruments in church worship. It never really dug Duke Ellington or Bix Beiderbecke – and it certainly did not advocate the jazz-dancing that Piet enjoyed in clubs from Paris to New York. The great paintings he made from then until his death, such as Broadway Boogie Woogie, are jazz on canvas.

Calvinism holds that eternal life is pre-ordained for some, while the rest face damnation. Mondrian, turning from the religion of his father, was drawn to the new occult belief system that so appealed to Af Klint and many other creatives in the early 20th century. The Dutchman became attracted to theosophy after consulting Adriaan van de Vijsel for an astrological reading. Mondrian was born under the sign of Pisces on 7 March 1872, and according to his horoscope was “very susceptible and [had] psychic tendencies”. He was “able to feel things without being able to give an explanation of how this knowledge was obtained”.

Mondrian, like Af Klint, became involved in theosophical circles and their ideas permeated his art. In 1914, he wrote: “To approach the spiritual in art, one will make as little use as possible of reality, because reality is opposed to the spiritual. We find ourselves in the presence of an abstract art. Art should be above reality, otherwise it would have no value for man.” Later, along with Theo van Doesberg, he founded the De Stijl magazine and art movement, committed to non-representational art, which he saw as necessary to express universal beauty.

In the basement of The Hague’s Kunstmuseum, Laura Stamps, co-curator of the Af Klint-Mondrian exhibition, shows me some of the Mondrian works that are soon to hang in Tate Modern. Some buck against Mondrian’s idea of art: several scintillating canvases depicting Dutch dunes are travelling to London along with earlier paintings of windmills, trees and towers created by pre-horoscope Mondrian. For those who know the artist for his gridlike (or neo-plasticist) works made entirely in the studio, it is a revelation to learn he worked this way, outdoors and from life.

Ironically, both visionaries’ approaches to abstraction were made possible only by closely looking at nature. Af Klint painted horse’s cheeks for veterinary surgeons; Mondrian drew bacteria under a microscope for researchers at Leiden University. Moreover, both were accomplished botanical artists: Af Klint produced a particularly beautiful book called Flowers, Mosses and Lichens; Mondrian repeatedly painted chrysanthemums. Tate Modern’s exhibition will, through 250 works, show that both artists developed their own visual languages and codes to make sense of the forces they believed drove life forward.

“Abstract art is not the creation of another reality,” said Mondrian, “but the true vision of reality.” Meanwhile, Af Klint reckoned: “Those granted the gift of seeing more deeply can see beyond form, and concentrate on the wondrous aspect hiding behind every form, which is called life.” For those who don’t have that clairvoyant gift and haven’t heard the voices of angels, there are, fortunately, other earthlier pleasures – not least the sheer beauty these two abstract art pioneers left in their wake as they toiled to make the invisible visible.

1 year ago

65

1 year ago

65

English (US)

English (US)