A 95m-year-old dinosaur skull discovered in Winton, Queensland, has been identified by palaeontologists as the first nearly complete sauropod skull ever found in Australia.

The skull belongs to a Diamantinasaurus matildae dinosaur, nicknamed Ann, that lived between 95m and 98m years ago. It is only the fourth specimen of this species ever discovered.

The study’s lead researcher, Dr Stephen Poropat of Curtin University, said it was “really amazing to be able to find a skull at all – they’re quite rare, and even more so to get so much of one that had been preserved”.

Sauropods were a group of long-necked dinosaurs that included Brachiosaurus and Brontosaurus. They had small skulls relative to their body size, with delicate skull bones.

“They would have been a good target for a predatory dinosaur or even a scavenging animal,” Poropat said. “They would have looked at a sauropod carcass and [thought]: ‘The easiest thing to take away is their head.’”

He said that with previous sauropod discoveries, “You’ll sometimes follow a string of neck vertebrae and come to nothing at the end of it because the head had gone.”

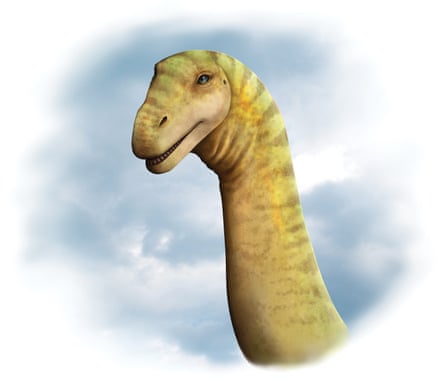

Diamantinasaurus matildae was a titanosaur, a type of sauropod that included the largest land animals in historical existence. The discovery of the Diamantinasaurus skull enables scientists to recreate for the first time what the dinosaur’s face may have looked like.

“In some ways, the head looks very much like that of Brachiosaurus,” Poropat said, noting there were some differences in shape and its teeth.

“Because [Diamantinasaurus] has a rounded snout instead of a squared-off snout, we can say it was a generalist browser – it was not feeding close to the ground habitually.”

“When we see sauropods that were low feeders, they tend to have much narrower teeth, they tend to have snouts that are sort of squared-off, almost like vacuum cleaners.”

The Diamantinasaurus skull had many similarities to another titanosaur, Sarmientosaurus musacchioi, which lived in South America around the same time. “You could almost put Sarmientosaurus’s head on Diamantinasaurus’s body and barely be able to tell the difference,” Poropat said.

The researchers believe the discovery reinforces a hypothesis that during the mid-Cretaceous period – 95m to 100m years ago – sauropods traversed between South America and Australia, using Antarctica as a pathway.

“Because the world was extremely warm … the poles were vegetated, not covered in ice,” Poropat said. “It would seem that sauropods took advantage of this really warm period.”

after newsletter promotion

Ann likely measured 15 metres to 16 metres long from head to tail. The maximum size for Diamantinasaurus is about 20 metres long, 3 to 3.5 metres high at the shoulders, with a weight of 23 to 25 tonnes.

“As far as sauropods go, they’re medium-sized,” Poropat said. “The largest [sauropods] push 40 metres in length and 80 tonnes in mass.”

The Diamantinasaurus skull was found during a dig in 2018 but has remained unreported until now. The process involved taking off topsoil after finding bone fragments at the surface.

“We started finding mostly limb bones and vertebrae, but around one of the limb bones there were scattered small bones and … it was hard to place what they were,” Poropat said.

Mel O’Brien, a volunteer, then found “a really weird-looking bit of bone that we eventually realised had to be a brain case. That then made all the other bits fall into place – we realised that we had a skull that had basically exploded and the bits were scattered around the back leg bones.”

The excavation was conducted in collaboration with the Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum of Natural History, citizen scientists and volunteers.

The study was published in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

1 year ago

92

1 year ago

92

English (US)

English (US)