On 24 February 2022, the day Russia mounted its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Oleksandr Lukianov went to work – but it was anything but a normal day at the office.

He and a small group of colleagues at the National Museum of the History of Ukraine in Kyiv, where he is senior researcher, hurriedly started to dismantle the exhibits, sending some objects to safer locations in the west of the country, and storing others in the basement. The group of curators ended up living in the building for two months.

At one point he looked out of the museum’s huge windows, which overlook the Dnipro valley from on high, to see bursts of light in the sky: a Russian helicopter being hit. As the days wore on, “I could hear the shots and bangs coming from Irpin and Bucha,” he said, referring to the nearby towns that Russian forces occupied in the early weeks of the invasion.

Eventually the galleries, once filled with 20,000 objects from the museum’s 800,000-strong collection, were empty. Gone was the finely worked gold from the ancient nomadic people of the steppes, the great horsemen, the Scythians. Gone were the coins, manuscripts and maps; gone were the ceramics from the ancient Greek colonies on the Black Sea.

“I thought it would never change,” he said, remembering the reassuringly immutable rooms of the museum where he had worked for seven years. “But here we were.”

And then he began to fill the museum back up again.

On 7 April, in the sunshine of a warm spring day, Lukianov and a small team of colleagues set off to Irpin, from which the Russians had withdrawn little more than a week before. Their mission: to collect new artefacts for the museum. “First in was the army, then it was the legal experts – and then it was us,” he said.

The first thing they saw was a burnt-out Russian army vehicle from which they retrieved damaged helmets and goggles. “We were overexcited at this point – we took everything we could. But then later we saw another, and another – so we started to be more selective,” he said.

The violence was appallingly fresh. “We did see and smell decaying bodies, and we saw unexploded devices,” he said. “But our curiosity overcame that – and so did the desire to look for history. The hardest thing was to see civilian cars that had been hit, and to understand that people, including children, had certainly died in them.”

The objects Lukianov and colleagues collected that day – including half-destroyed signage from a pharmacy, a Russian soldier’s boot, a 1970s dosimeter for measuring radiation levels as the invading convoys passed through Chornobyl, and Russian ration packs – now form the basis of a display on the museum’s ground floor.

Added to the objects brought by the curators are a number of artefacts donated by the military and local residents. Among them is a set of guidelines, apparently issued to occupying soldiers, on how to interact with locals.

“If they ask if you are Russian or Ukrainian, say, ‘We are both Russian and Ukrainian, and most importantly we are all Orthodox Christians’,” the document suggests. “If they start to argue, talk about gay parades and the decay of orthodoxy … Never mention the word ‘war’ – if they ask about war, talk about the police and local administration.”

Soon after, on 23 April, Lukianov went on another collecting mission – this time to a window factory near the town of Dymer, north of Kyiv, which had been repurposed as an HQ by the invading forces. The first thing that hit him, he said, was “a very strong smell of faeces – you couldn’t imagine how they were living there.”

after newsletter promotion

Items from the factory include a discarded copy of the Russian Red Star newspaper, dated Wednesday 16 March, and, remarkably, a road atlas of Ukraine dating from 1975. They found photographs of women – girlfriends, wives – and the start of a letter to a loved one beginning, “Hi Zhenya, Now, there is no …” and then tailing off.

It was important, Lukianov said, to collect objects as quickly as possible after the areas were liberated. It was the museum’s responsibility to keep and store these vestiges of violence, as grim news passes into vital historical memory. “The sooner we do it, the better. When we went on our second mission, already something was lost – things had been removed by the local community and the army.”

The natural instinct was for the clean-up operation to start as soon as possible, he said. “People don’t want to keep things with negative memories. But it’s our job, and the better we capture the situation now, the easier it will be for those who come afterwards to research and understand this period.”

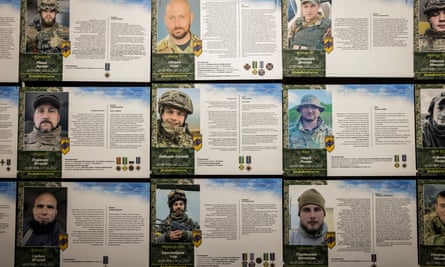

To mark the anniversary of the full-scale invasion, on 24 February, the museum opened a new exhibition about last year’s devastating siege of the Avozstal steel plant in Mariupol. “It is a very emotional exhibition for us,” said museum guide Natalya Lykhytska. “Every day parents of those killed come and leave flowers here. It used to be Scythian artefacts in this hall – now it is war, war, war.”

The museum’s latest exhibition, which opened earlier in April, is about the village of Iahidne, on the outskirts of Chernihiv in northern Ukraine, where 368 inhabitants were forced into the cramped basement of the primary school for over a month, enduring terrible conditions, while the invading Russians used the upper parts of the buildings as their headquarters. The display includes children’s drawings and toys, and a reproduction of the walls of the basement, on which those held there chalked up a tally of the passing of the days – and of those who died.

There hasn’t been the chance for a collecting trip in a while, but new donations come in every day. When the Guardian visited, Lukianov had just received a stash of diaries kept by Ukrainians under Russian occupation – he hadn’t even had a chance to look at them yet.

“I studied history: when I was a student, it was easy to think that history happened to other people at other times. Francis Fukuyama declared the end of history,” he said, referring to the American political scientist’s famous pronouncement at the end of the cold war. “It turned out he was wrong.”

1 year ago

94

1 year ago

94

English (US)

English (US)