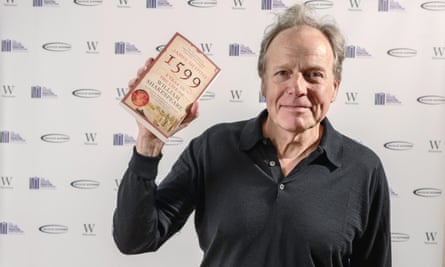

Serendipity dictated that the American writer and academic James Shapiro received the Baillie Gifford prize for nonfiction’s Winner of Winners award, given to celebrate its 25th year, at a ceremony in Edinburgh. In his teens and early 20s, Shapiro tells me as we talk over Zoom the morning after his victory, he would often hitchhike from London to the Edinburgh festival as part of his immersion in the plays of Shakespeare. This period in his life sowed the ground for his acclaimed book, 1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare, first published in 2006. He was, he explains, recovering from the “awful experience” of studying the playwright in middle school; every summer for several years, he would save up enough money to come to the UK on a Freddie Laker plane, “where you could fly from New York to London for $100 round trip and sleep in church basements and for 50p see spectacular productions”.

In London, Stratford and Edinburgh, he’d see 25 plays in as many days, “and they’re all tattooed inside my skull to this day. The greatest one I saw was Richard Eyre’s Hamlet at the Royal Court in 1980 or so. Richard wrote me a note this morning, and it was so moving to me because that’s where it came from, seeing productions like his.”

Shapiro is passionate about viewing Shakespeare through the lens of performance, the better to understand how central political and social context is to his work. He is currently advising on Tony Award-winning director Kenny Leon’s production of Hamlet for the Public Theater in New York, set in a post-Covid 2021 and starring Ato Blankson-Wood as the prince. It is, says Shapiro, “a Hamlet that speaks to the now. And I have the street cred, as we say in Brooklyn, to tell Shakespeare purists, whatever that means, that these plays have always spoken to the moment. And to think that what Olivier did or Kenneth Branagh for that matter is where Shakespeare stops, is to be as unShakespearean in one’s thinking about Shakespeare as possible.”

His vision for 1599, a microscopic look at the critical year in Shakespeare’s life when he was working on Henry V, Julius Caesar, As You Like It and the first draft of Hamlet, was not initially endorsed. His application for a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities in the US in the late 1980s was turned down twice, he remembers. “I wasn’t discouraged by that. I just felt they didn’t understand that I was trying to do something different.” The “something different” was to understand the immense anxieties of the age: the country poised on the brink of invading Ireland with a 16,000-strong force; the fear that Elizabeth I’s reign was approaching its end with no clear successor in sight; the strengthening possibility of another Spanish Armada. It’s no coincidence, says Shapiro, that Hamlet opens with men on the ramparts, nervously watching for hostile forces.

He was also frustrated with an academic orthodoxy that relied on speculation and anecdote, as well as an outmoded concept of the playwright: “The Shakespeare that existed when I was writing that book was still very influenced by Coleridge’s sense that Shakespeare was from another planet, or Ben Jonson’s line: he was not of an age but for all time. And that just struck me as completely wrong.” Instead, Shapiro wanted to ground Shakespeare in reality, finding out what the weather was each day of that single year, who he met, where he travelled.

Shapiro is also a judge on this year’s Booker prize for fiction, and he is fascinating on the distinction between his work and that of novelists. He admires “the way that creative minds can tease out things that are less visible to those of us who deal in facts”. How does he feel about historical novelists – indeed, about a work such as Maggie O’Farrell’s Hamnet, a reimagining of Shakespeare’s family that has just been adapted for stage by the RSC?

He reveres Hilary Mantel, who was, he says, “a great historian, as well as a great novelist.” And he is, he replies, very happy for O’Farrell: “She deserves great success for that and for her more recent book, but it’s not a book that I can read comfortably, because it’s fiction.”

after newsletter promotion

“I draw a very sharp line between fiction and nonfiction,” he adds. “I think that the danger of fiction is to sentimentalise. So that’s one of the things that I’m extremely careful as a Shakespearean not to do. On the other hand, I understand how deeply people want to connect with Shakespeare the man, with Anne Hathaway, with Judith Shakespeare: they lived, they died, their internal lives went largely unrecorded. And it takes a talented writer to bring that to life. But that’s not the stuff that I do. I don’t write that; but somebody needs to.”

His next work is called Playbook, and will focus on America’s Federal Theatre Project of the 1930s, a progressive attempt to bring drama to mass audiences that was targeted by the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Then, as now, and as in the 16th century, theatre is powerful, and Shapiro intends to do everything he can to defend it.

1 year ago

72

1 year ago

72

English (US)

English (US)